Nem bem o post aí de baixo ficou velho e saem os resultados de uma pesquisa com nebulosas planetárias que são bem interessantes.

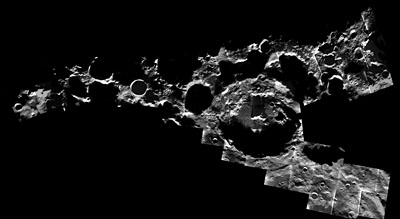

Nem bem o post aí de baixo ficou velho e saem os resultados de uma pesquisa com nebulosas planetárias que são bem interessantes.Como eu escrevi, cada nebulosa planetária revela uma surpresa: no geral têm quase sempre o mesmo aspecto, mas cada uma tem detalhes próprios. Na maioria das vezes, como na NGC 2371 abaixo, esses detalhes acabam sem explicação, apenas boas hipóteses. Agora, uma equipe de astrônomos da Universidade de Rochester, nos EUA, diz que tem uma outra explicação para a grande variedade de nebulosas planetárias observadas e esta explicação tem a ver com… planetas!

Pois é, você viu aí que o termo nebulosas planetárias foi cunhado há mais de 200 anos, na época em que objetos como esses estavam sendo descobertos. Isso porque aos telescópios da época as nebulosas planetárias lembravam em muito o planeta Urano. Depois de um tempo ficou claro que essas nebulosas não tinham nada a ver com planetas. Agora, depois de muito tempo, parece que as coisas não são bem assim.

Os argumentos da equipe liderada por Eric Blackman são bem interessantes e plausíveis. Funciona assim: as estrelas que originam as nebulosas planetárias são estrelas com pouca massa, tipo o nosso Sol, e não é difícil encontrar planetas em estrelas deste tipo. Temos aí centenas de planetas descobertos em estrelas assim, planetas gigantes gasosos muito próximos das estrelas (os "Hot Jupiters") ou até mesmo indícios de planetas rochosos. Durante a expansão das camadas externas das estrelas, nos momentos finais de suas vidas, a presença de planetas ajudaria a moldar a nebulosa que vai ser ejetada.

Dependendo do tamanho dos planetas e a distância deles em relação à estrela, diferentes formas poderiam ser criadas. Um planeta grande e distante poderia formar uma barreira de gás e poeira que produziria uma "cintura", dificultando a expansão do gás na região do equador da estrela. Isto resultaria em nebulosas deformadas, sem a forma esférica esperada. Planetas mais próximos da estrela poderiam efetivamente bloquear a expansão do gás no equador, favorecendo os pólos como rota de fuga. Nebulosas formadas assim teriam a forma de ampulhetas e em última análise este seria o mecanismo de formação de jatos nas nebulosas.

Tudo isso vem de simulações numéricas, isto é, ninguém viu um planeta em uma nebulosa planetária. Mas é uma idéia interessante e essas simulações conseguiram explicar a forma de M27, a primeira nebulosa planetária descoberta (na foto acima). Além do mais, é uma hipótese de fina ironia, afinal temos dito nesses últimos 300 anos que "nebulosas planetárias nada têm a ver com planetas"!

March 10th, 2008 at 3:49 pm "Guedes and his co-author Gregory Laughlin…"

Minor point, but it's pretty likely that with the name "Javiera," Guedes is a woman.